Selected essays published here, plus links to ongoing work at Temple of Liberty.

Weekly writing at Temple of Liberty → https://templeofliberty.substack.com

On (Not) Becoming an Architect

Architecture didn’t seem to be working for me, and I didn’t have a Plan B.

But the Marines did.

So I enlisted to “see the world,” and find whatever it was that I was supposed to do with my life besides being an architect. And what I found, I pursued for more than the next three decades.

I didn’t become an architect, but I never stopped thinking like one.

Frank Lloyd Wright’s Fallingwater, Bear Run, PA.

I didn’t become an architect. But the builder in me never stopped drafting.

A personal essay about usefulness, beauty, and the long arc of a second act.

Wood crackled in the fireplace, hot embers riding thermal updrafts and disappearing into the blackness of the chimney above. Meanwhile, small sips of bourbon went down into my stomach, providing a different kind of burn, a pleasant one—smoky and smooth. My eyes were focused on the pages of a home design book spread open on my lap, reabsorbing some of the lessons I’d first learned at architecture school years before.

Form follows function. Start simple. Conceptualize the “business” areas of the home—kitchen, dining room, mudroom—as one cluster, and the “quiet” areas—bedrooms, reading corners—as another. Put the quiet rooms where they’ll actually be quiet. And don’t neglect the views. Where does the sun come from during different seasons? Where does it set?

But above all, I kept coming back to a basic truth I’d learned young: the site itself is our biggest asset. We can place the home, whatever its eventual design, on the site in any manner we choose—but how we do so, whether it’s in consonance with or in opposition to the land’s contours, the prevailing winds, and how the sunshine falls in winter and in summer—that will be the main struggle.

***

Like a lot of things in my life, it all may have started with a book.

When I was in the seventh grade, I discovered David Macaulay’s books. The first one may have been Castle, or it may have been Cathedral. I don’t remember for certain. What I do remember is loving those giant, oversized books filled with black-and-white hand-drawn pictures of structures, showing different stages of their construction chronologically—and in the case of cathedrals for sure (probably also for castles), noting how their design and assembly were huge, long, multi-generational undertakings lasting decades and, in some cases, centuries.

It was amazing to me then (and still is now) that such sustained, focused commitments were possible, particularly when their aim was to create places for people to inhabit—for worship, for living, for interaction. These herculean efforts created spaces of beauty and aesthetic value, even grandeur. And Macaulay’s drawings (I always thought of him first as an artist and illustrator, but I recently learned that he trained as an architect, though he chose to never go into practice) also included depictions of the surrounding environment—smaller houses, shops, and markets around the periphery of the great building that was the focus of his books—a continual reminder that any work of architecture exists in conversation with what’s around it. A building succeeds or fails by how people relate to its structure and the spaces it creates.

From that point until I dropped out of college to enlist in the Marines at nineteen, I was convinced I would become an architect. I reveled in making drawings of structures—almost always residential housing in my case—learning the rudiments of architectural and engineering drawing by hand, semester after semester of multi-period drafting courses in high school, and then learning the then-relatively new ways of computer-assisted drawing (CAD) as a freshman and sophomore in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s pre-architecture program.

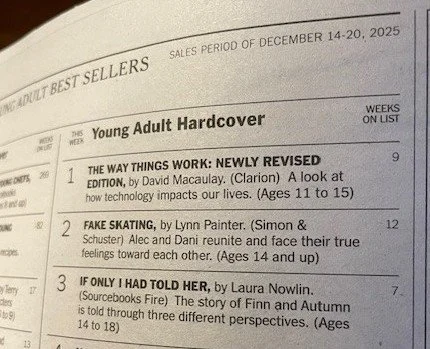

Macaulay recently took me by surprise: he is apparently still making books. I learned of this the old-fashioned way—by looking through the New York Times best-selling book lists printed each week in the back of The New York Times Book Review (NYTBR).

I’ll admit that as someone who has long enjoyed writing—and has the seeds of several books knocking around in my head at any given moment—I look at those lists for more than one reason. First, and most obviously, to see what’s selling and therefore what I might be missing in my own reading of fiction and nonfiction. But second, and more secretly, I imagine what it would be like to open that list one day and see a book I wrote listed there. (One can dream…)

Every week, along with the standard lists, the NYTBR includes a rotation of lists from various sub-genres and types: audiobooks one week, then graphic novels and manga, and so on. This particular week, the rotation landed on “Young Adult Hardcover,” and lo and behold, right at the very top of the list—#1 bestseller—was David Macaulay’s The Way Things Work: Newly Revised Edition.

A surprising discovery.

What?!? Bells went off in my head. The page sort of floated in front of my eyes. That book had apparently been on the bestseller list for nine weeks running. Nine weeks!

When I first discovered David Macaulay’s books on the metal shelves of my junior high school in the late 1980s, they already seemed a little…older. They certainly weren’t on any “new releases” shelf. They were as old or older than I was, and well-worn, as if a lot of patrons had sampled the material over the years. And if you check the publication dates of Castle or Cathedral, you’ll see the mid-1970s. So yes—this threw me.

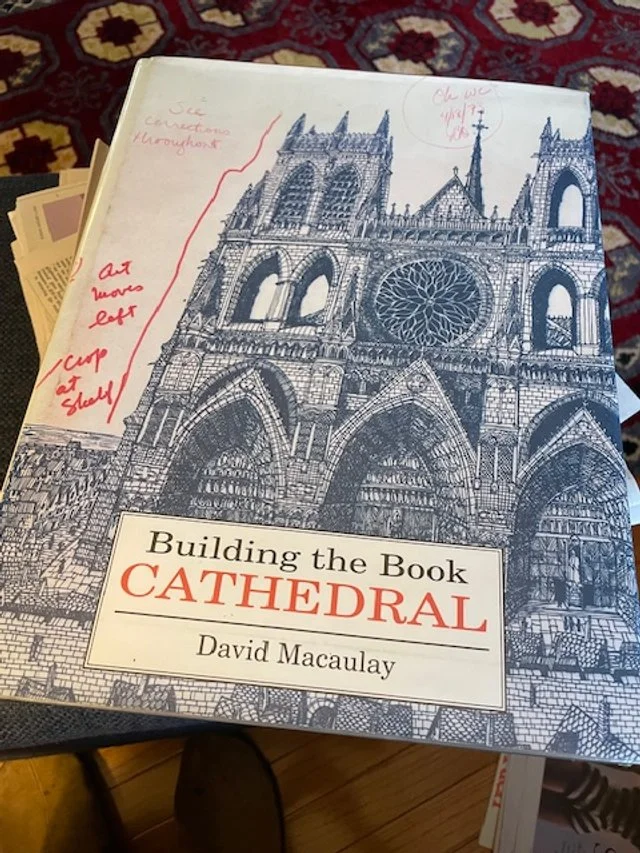

Not long afterward, this discovery motivated a visit to my local library, where I found some of Macaulay’s giant books waiting for me after all these years.

When I got there, I didn’t go to a computer terminal to search the catalog and immediately confirm or deny that any such books were on the shelf. I wanted a little mystery. Instead, I did my standard browse, starting with the new nonfiction books, and as I did so, I naturally came upon the new books on art, architecture, home and garden, and the like. Noting the call-number range, I then approached the stacks to begin a sweep of the appropriate areas.

I browsed lightly, and within moments, I thought I spied a few shelves down the signature oversized outline of a Macaulay book. I felt my breath catch in my throat as I worked my way up the aisle—could it really be? And as I drew closer, it was confirmed: this was certainly a Macaulay book, about cathedrals—but wait…this was somehow different from the version I remembered from my youth.

I was now close enough to bring it down from the shelf. My hands reached out, I gripped the volume, and I pulled it down, rotating it so I could clearly gaze upon the enormous cover and its art.

Building the Book Cathedral, it said.

The book I found at the library.

How is this different from the Cathedral book I knew as a youth? I thought. How is it the same?

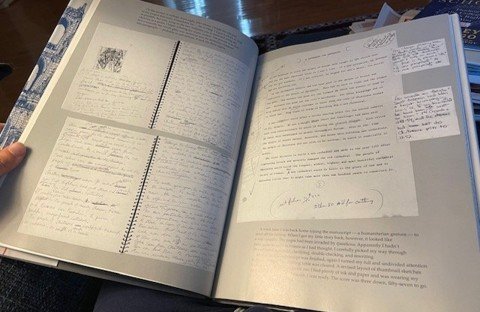

I swung open the massive front cover like the door of a building of great importance and waded in, leafing through the substantial pages until I got to one that showed an image of a draft page from the original version of Cathedral, marked up in pen and pencil by members of the editorial team at the publishing house.

Behind-the-scenes: how the book was made.

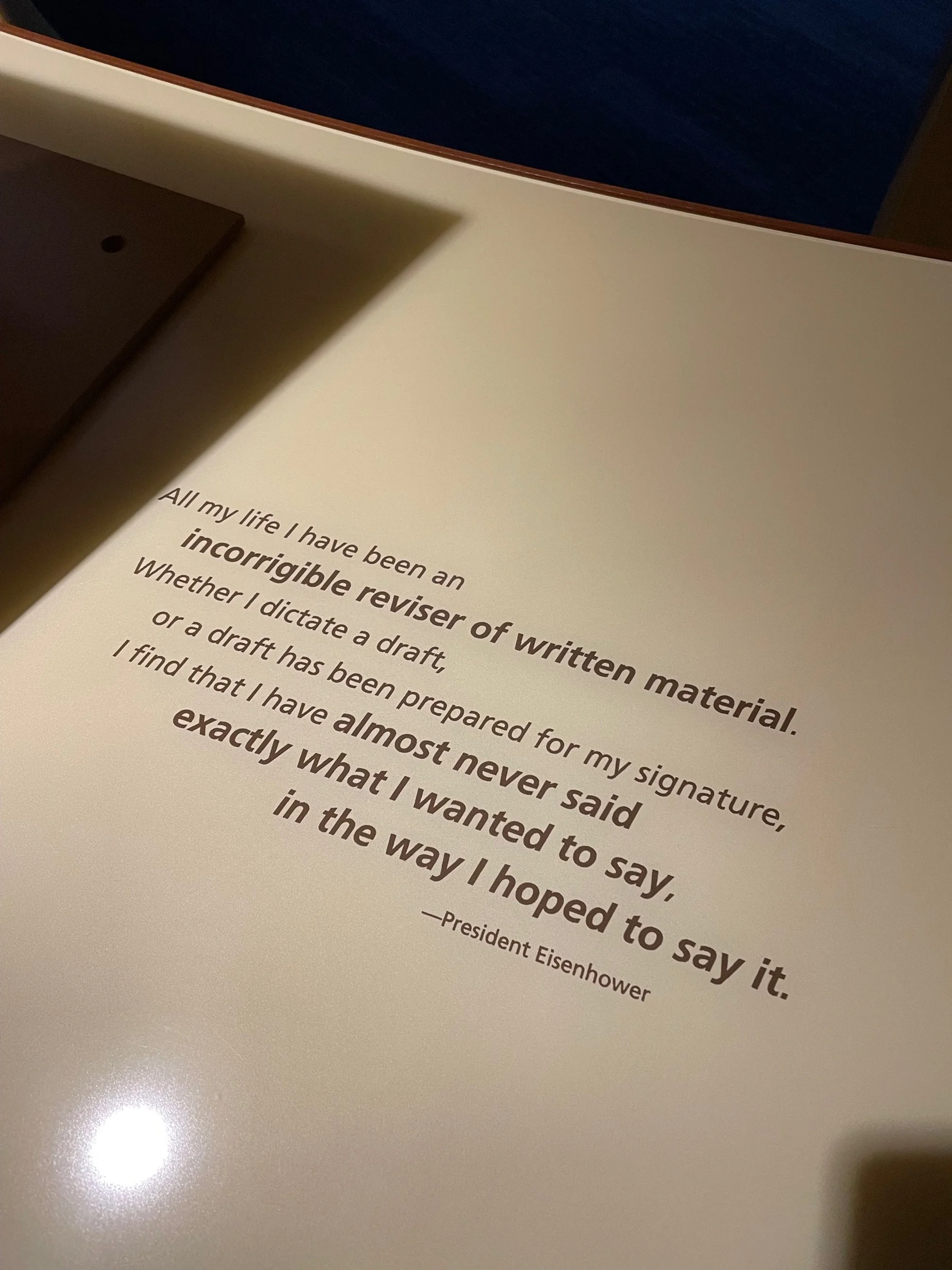

It reminded me quickly that all good writing is rewriting. Almost nobody sits down and cranks out finished prose the first time around (this author certainly included). And so it apparently also was with David Macaulay.

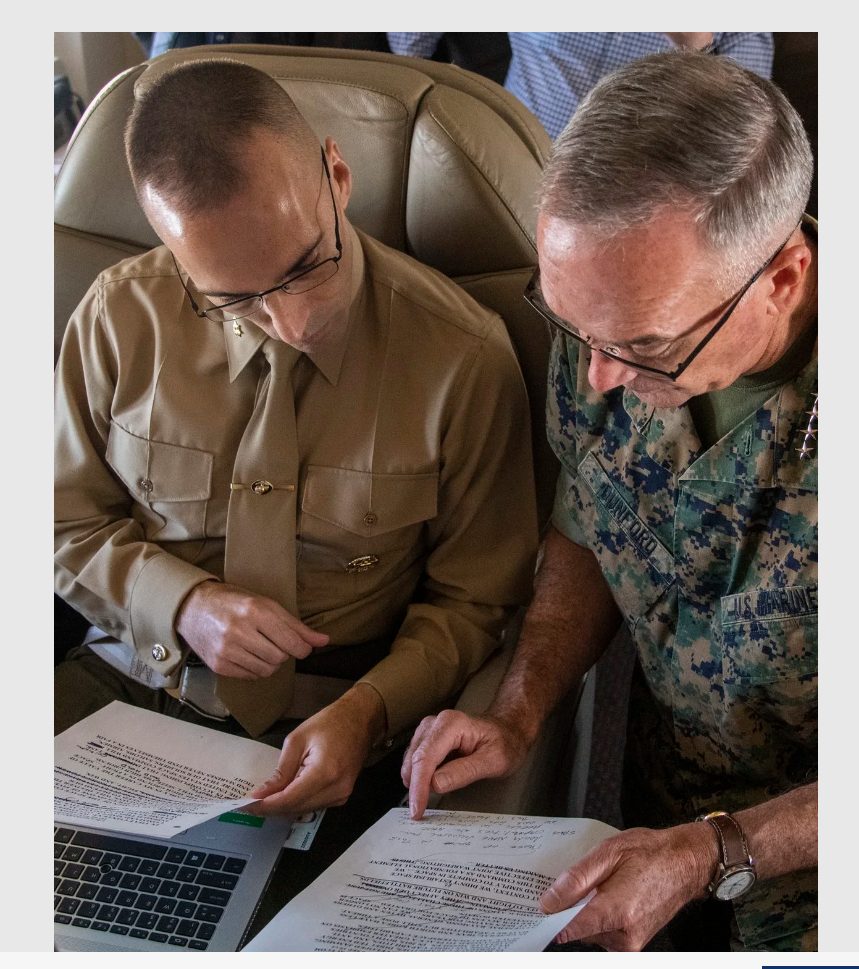

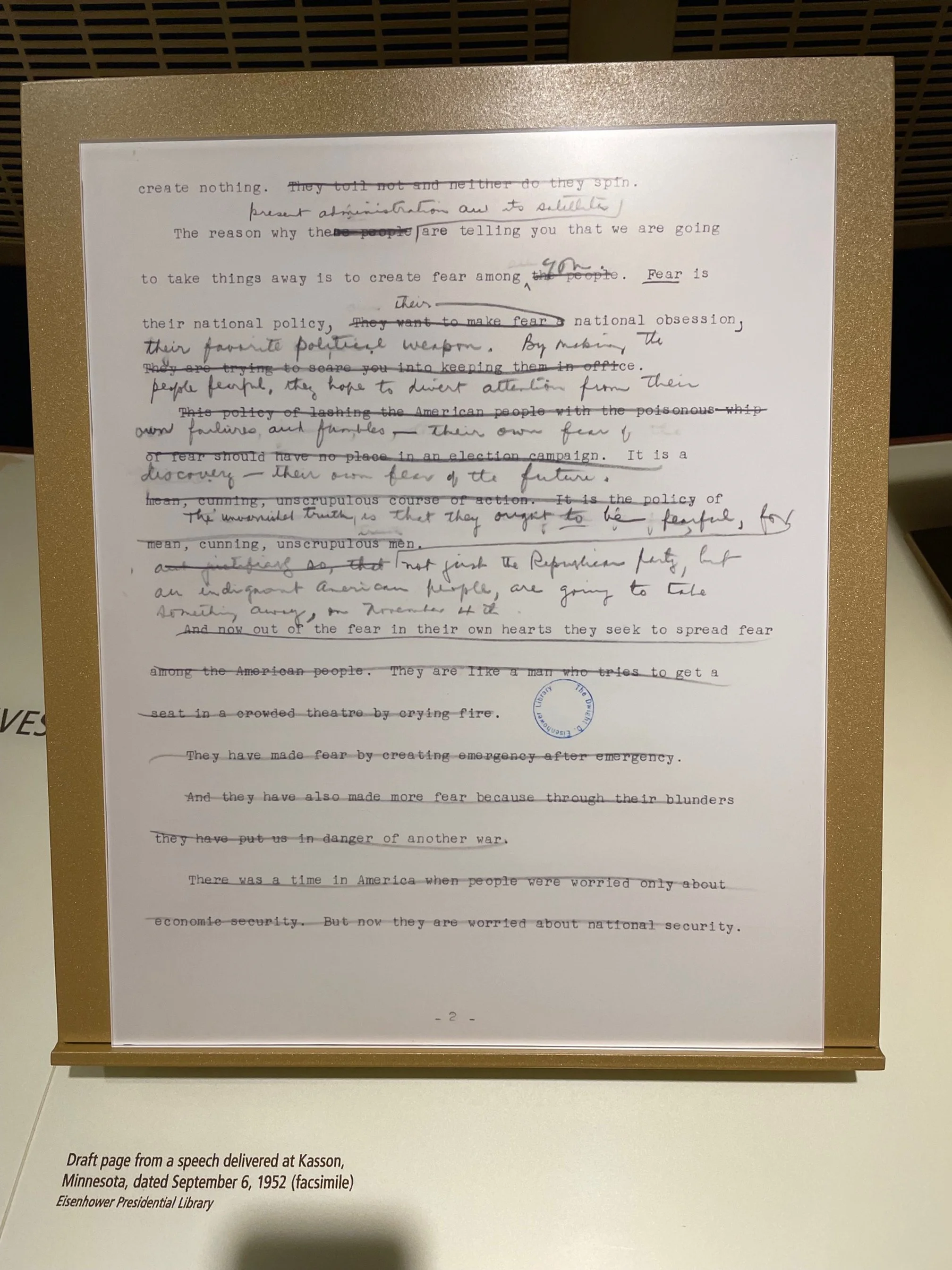

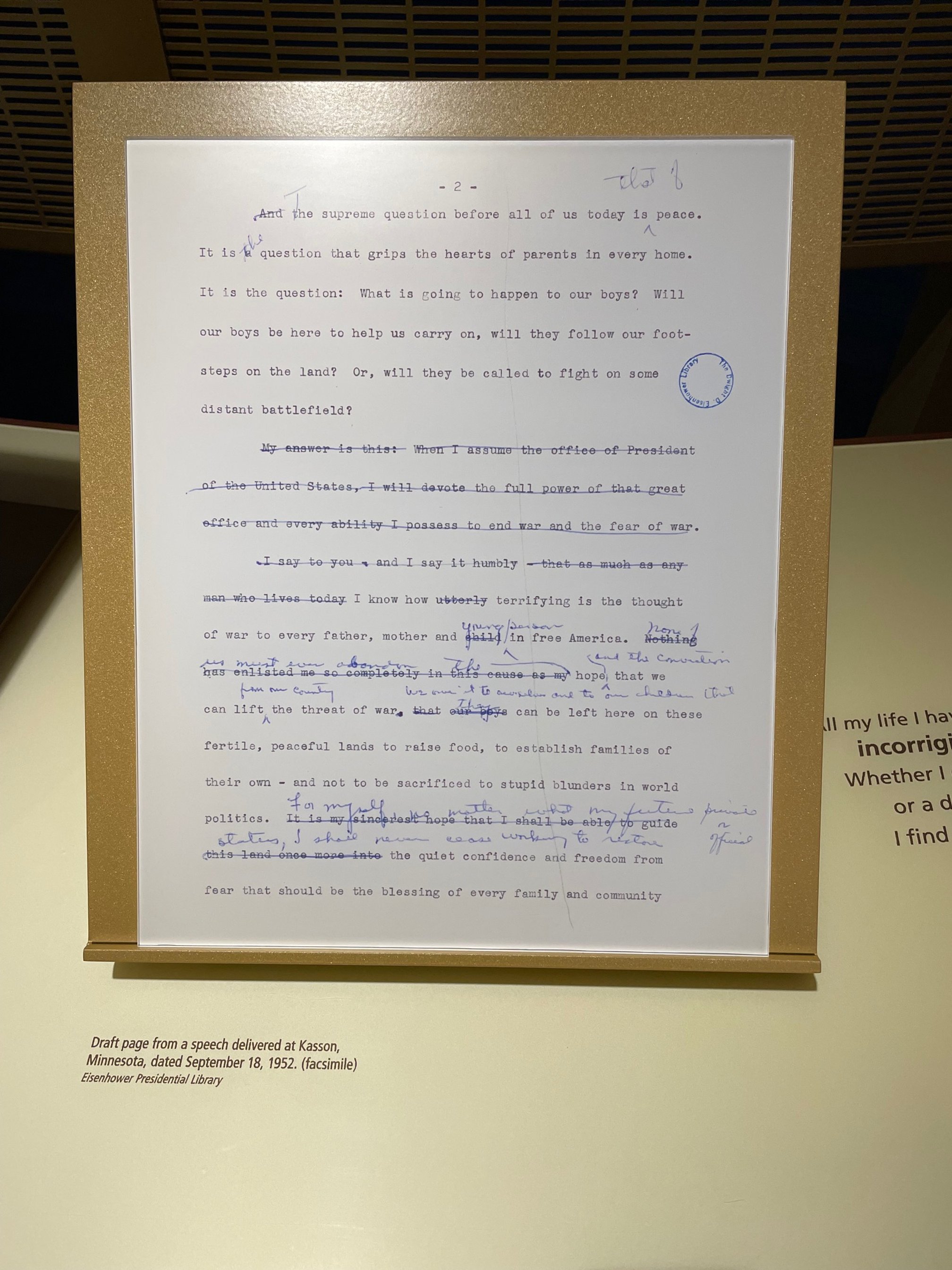

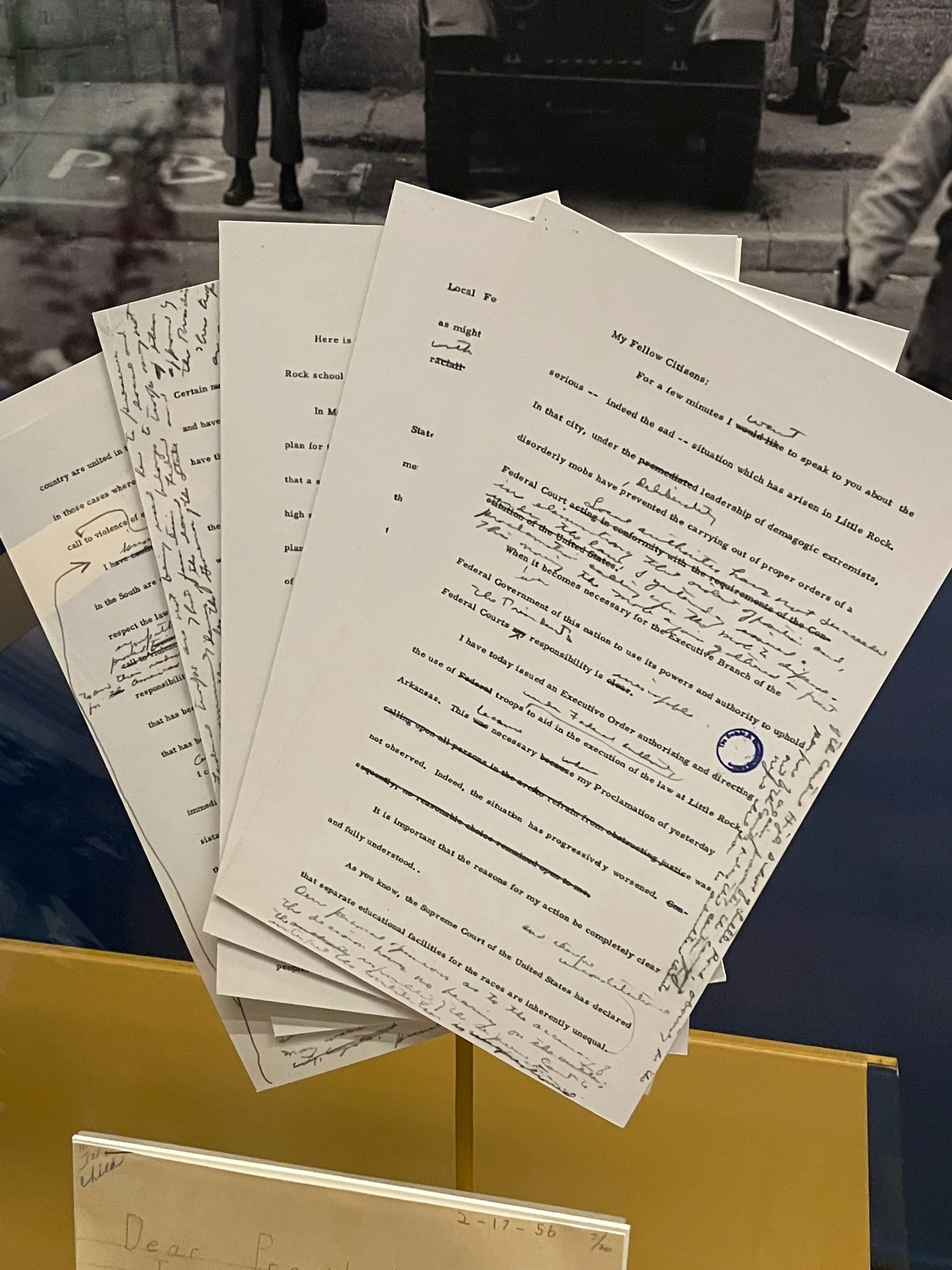

The marked-up pages helped tell the journey of that book and how it was published—the process, the path, the trip-ups, the re-dos. And the marked-up pages were like catnip to the former Pentagon speechwriter in me. When we were lucky, that’s what we’d get back on drafts submitted up the chain—handwritten feedback, clarification, edits. It illustrated (literally) the back-and-forth that went into polishing the prose, which, for important pieces, could run into the dozens of versions and revisions. The message had to be just right. A lot of equities were in play on every aspect of the speech text.

The author receiving some direct feedback on a draft speech, 2019.

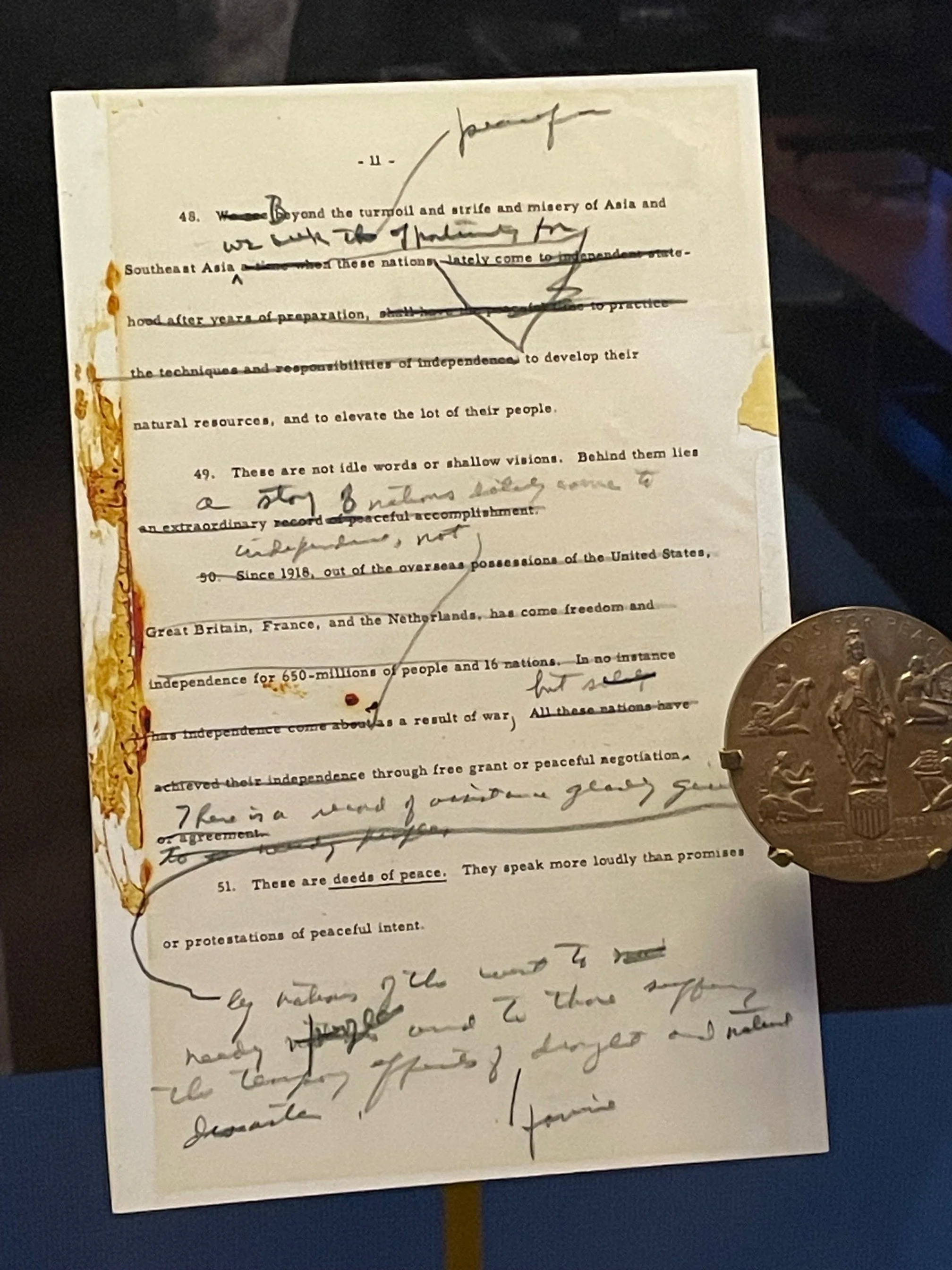

I could recall seeing similar marked-up drafts in archives I’d visited during my dissertation research—James A. Baker’s papers at Princeton, displays at the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum in Abilene, Kansas, and even a display of Pete Souza’s photographs from the Obama administration I’d visited somewhere along the way. Different leaders, different contexts—but the same reality: public words are almost always forged through dialogue.

Speech-related images from the Eisenhower Presidential Library and Museum, Abiliene, KS.

And of course, there was the other thread calling to me from what I was seeing on the pages: the inner architect. As I looked over Macaulay’s black-and-white pen-and-ink drawings, especially the early draft drawings he shared (ones that didn’t make it into the final version of the book I’d first read so many years before), I thought back to my architectural training, and how I’d sometimes chafed at the changes I needed to make to a floor plan, an elevation view, a sectional view.

Most of what I’d done in this regard was manual drawing on a drafting table (remember, CAD was new), so there were piles and piles of eraser dust surrounding me as I took away the old and replaced it with the new, always hoping not to tear a hole in the paper in the process. In drawing as well as writing, good work is re-work.

And perhaps it is that way in life as well. Our initial efforts at almost anything often come up short—but we try, try again. “Fall down seven times, stand up eight.”

Not long after I brought Macaulay home again, I found myself in another kind of archive: the National Building Museum, in Washington, D.C. In a display case labeled “Drafting & Drawing” were tools like the ones I’d once used without thinking—an eraser shield, a horsehair brush, compasses, a T-square. I stood there longer than I expected, peering down at these items, remembering. It wasn’t nostalgia, exactly. It was recognition. The inner architect doesn’t announce himself. He just notices what most people walk past.

***

I left architecture for two reasons: first, a song.

Yes, a pop song.

It was Toad the Wet Sprocket’s 1991 “Walk on the Ocean.” Long story short, one of my architecture professors assigned students a project: listen to that song and create a physical object that explains or illustrates it.

You can see the problem here. One must listen to the song many times—not just the lyrics, but the melody, the way the sounds are layered and mixed, the instruments, the mood—and then translate all of that into something physical. I didn’t really care for Toad in the first place (my tastes then were mainly heavy metal), and having to subject myself to that song dozens—if not hundreds—of times was bound to end badly. In the end, I submitted a project. It didn’t fare well.

That assignment was the moment I began to question my path. I loved the drafting and the drawing process for floor plans, elevations, landscapes, all that. But my eighteen- and nineteen-year-old self couldn’t see how the more artistic sides of the schooling contributed to that. I get it now. It just takes some people longer.

So there was drift. I was still getting good marks overall, and I was enjoying other courses like history and other general-purpose courses. But the architecture thing—at least the way they were teaching it then at the UNL School of Architecture—seemed like it was going in a direction I was no longer comfortable with.

The second reason flowed from the first: architecture didn’t seem to be working for me, and I didn’t have a Plan B.

But the Marines did.

So I enlisted to “see the world,” and find whatever it was that I was supposed to do with my life besides being an architect. And what I found, I pursued for more than the next three decades.

***

I didn’t become an architect, but I never stopped thinking like one.

In the summer of 2017, when my family and I were moving from our duty station in Okinawa, Japan to Boston for me to begin my PhD studies at Tufts, we stopped at home in Nebraska to visit family on the way, as we typically did between assignments. From the plains, we drove east in my 2009 Pontiac GXP sedan, which eagerly gulped down the miles on the open road. Road trips seem good for the soul—especially after having spent the previous three years living on an island situated on the edge of the East China Sea smaller than a single county in Nebraska.

Plotting the route, I made a point of including a stop at Frank Lloyd Wright’s magnum opus, Fallingwater, along the way. Ever since I’d first heard of the home perched above a waterfall in southwestern Pennsylvania as a teenager making floor plans, drawing elevation views, and building scale models of houses, I’d always wanted to see it with my own eyes.

That kid back in Nebraska had never flown on a plane and rarely left the state except for the routine visits to extended family not far across the Missouri River in north central Iowa during school breaks. Later, I would routinely travel and live overseas. I would end up embarking on advanced graduate study in international relations. And still, deep down, I loved architecture.

So the stop in 2017 was, in many ways, more pilgrimage than standard household move.

When we arrived at the site, situated in the Bear Run Nature Preserve, we parked the car and made our way on foot to the visitor’s center and gift shop, where we purchased admission tickets. As we continued from there down a gravel path through the trees, I eagerly anticipated our quarry—we still hadn’t caught a glimpse of it, due to the dense foliage of the nature preserve all around us. Being summer, all was leafy and green.

Rounding a corner, it finally came into view through an opening in the trees: all horizontal lines, light brown in color, the signature cantilevered decks extending over the falls of Bear Run with no visible supports or anchors.

Magnificent.

One could barely tell where nature ended and the house began.

At Fallingwater, 2017.

We asked a person standing nearby to take our family photo with the house in the background. We all posed. I smiled. I could feel the inner architect stirring—but I also knew he would need to stay inside for a while longer. I had a few more years (at least) of grindstone work ahead of me. Fallingwater would have to hold the place of a promise for the moment.

***

The other night at an alumni party in DC, I was speaking with a friend who works on Capitol Hill, who I had last seen in late spring last year, not long before I retired from the Marines. It took him a minute to calibrate his eyes to my new, post-retirement appearance featuring longer hair and a full beard. Others have told me I look very professorial—which I am not opposed to.

We chatted and caught up, and then he asked, “Are you traveling? Are you getting out to see things?”

I paused—because yes, quite a bit of traveling. But the places I find myself seeking out aren’t always what people expect. I told him about bookstores and libraries, focusing on the latter because, quite frankly, they’re the more spectacular of the two. Some might think I go to the libraries for the books—and that’s not wrong. But the two-in-one value I get from many public libraries is that, in addition to the books and periodicals, the central libraries of many American cities (and those abroad) are also exquisite architectural specimens.

The best example that comes to mind is the central library in Minneapolis. It is an amazing space of poured concrete, glass, wood, and steel, assembled around a common central atrium that must rise to most of a hundred feet. St. Louis, Baltimore, and Washington, DC belong in the same sentence, too. And these are just the ones I’ve been to in the past six months.

When I visited my parents back in Lincoln recently, the local news ran a segment about an initiative to fund a replacement for the aging central library downtown. The numbers were big enough to make my mother suck wind in through her teeth—$46 million for the plan on the table, and higher figures in earlier options.

I immediately said: fund it. That earned me a disapproving look from my parents. My father rolled his eyes.

It’s easy for me to say that—I don’t live there anymore, and I won’t be on the hook for it. But I can say this with clarity: great cities—and great societies—create monuments to learning and knowledge. We call them libraries. And we need more of them, not less.

***

The inner architect never left me. He was there at Fallingwater. He was there again when, several years later, I visited Wright’s house at Kentuck Knob, just a few miles away. I now see this second property as a model for siting our house-to-be on the land: set upon a hill, held back from the approach, with its best reveal reserved for the moment you finally round the corner and see what the place is really doing with the site.

That inner architect (not fully trained, certainly not licensed) is now helping design the “forever house” we will build on the Kansas prairie, probably using concepts and ideas from Frank Lloyd Wright’s prairie style. The inner architect was there all along, just dormant. For that insecure teen back in Nebraska, architecture provided a way of imposing order and purpose on the world around me. Then, designing a home was like building a future, imagining one into life. Perhaps it still is. Now, it provides a means of fusing a harmonious blend of nature and the man-made, between the site and the built—if it’s done right.

Once, during a Pentagon job interview, a senior official asked me, “What’s your origin story?” I stumbled around, thinking—is he asking for my military biography? So I started there. I didn’t make it far before he stopped me: “No, that’s not what I’m talking about.” Then he gave a brief example, discussing family roots, geographic origins, and so forth. I followed his lead. I don’t recall precisely what I said—I know it had nothing to do with architecture.

If I had more time in that interview, I think I would have answered differently. Not with a résumé, not with a chronology, but with a picture: a kid bent over a drafting table, eraser dust everywhere; and then, decades later, the same man sitting by a fire, turning a house over in his mind—sun angles, wind, quiet rooms, the long view. I didn’t become an architect. But I’ve learned that some parts of us don’t vanish. They go quiet. They wait for the right site.